The 404 Reports

Summaries of under-reported news, updates on previous Monitor stories

| The 404 Reports Summaries of under-reported news, updates on previous Monitor stories |

|

[Do not bookmark this page, as the 404 Reports address will change with each edition.] |

|

|

|

|

|

Newspapers won't really follow the town criers into history; non-newsprint versions like the Albion Monitor -- edited journals containing a variety of news for a general audience -- always will be around. The modern American newspaper may even be the last kind of print media to survive; even in an ultra-electrionic age it is still a thing of wonder, and until they come up with a way to jack a wire directly into your brain for instant download, there's not going to be a more efficient system for delivering the goods. From pushing the more important stories to the front of the paper to the inverted pyramid writing style of news articles, newspapers have evolved into the means of conveying the most possible amount of information as fast as possible.

Start with the familiar complaint that [insert important story here] didn't receive the big front page splash that it deserved. Despite declining readership and credibility, newspaper front pages are still totemic objects that shape the very news they report; even in this Internet age, a story's importance is often measured by the kind of front page coverage it receives.

No newspaper acreage in the world has more gravitas than the front page of The New York Times, and stories that appear there are treated as gospel. Even those who view the paper with scorn treat the Times' front page as an icon. When Ann Coulter wanted to show how East Coast snobs hated regular folk, she wrote that the Times didn't run a front page piece about the death of NASCAR star Dale Earnhardt for two days, and then pointed an accusing (but well-manicured!) finger towards an article that began, "His death brought a silence to the Wal-Mart." As usual, she lied -- a straight news story did appear on the front page the very next day, and what she thought was a snooty essay was authored by Alabama's Rick Bragg, winner of a Pulitzer for his descriptive coverage of contemporary American culture.

Every front page magnifies stories appearing there, and that's particularly true for The New York Times. Items from that page one will likely be broadcast on the evening news, summarized by the wire services, ripped-off by ten thousand bloggers, and otherwise spread everywhere. Times front page stories influence elections, national policy -- and even launch wars. Trouble is, when facts in those stories are wrong, the error is also magnified. A goodly part of the blame for the Iraq War goes to the Times' breathless 2001-2003 front page reporting by Judith Miller and others describing Saddam's hidden mad scientist biolabs and proto-atom bomb factories. Before that, there was the Times' 1999 libel against Wen Ho Lee, the naturalized American citizen accused of giving China some of America's nuclear secrets. Before that, there was the Times' error-ridden 1992 investigative report on Whitewater, which Clinton critics quoted in following years to "prove" the president was devilish. The trail of front page flubs goes back as far as you want to look; in 1920, Walter Lippmann and a colleague pointed out that the Times reported the Soviet regime had collapsed or was about to fall nearly a hundred times between 1917 and 1919.

There's lots more about front pages that sharks can thrash over; dedicated readers bicker about story placement above/below the fold, column inch count, and choice of photos like members of a crazed typography cult. Truly obsessive page-one junkies can even compare the shortcomings of their favorite paper to other front pages around the world at the wonderful Newseum website (select "map view" if you have a recent version of Flash). But the fundamental problem is that an erroneous front page story can do enormous damage that may be impossible to fix without extraordinary efforts; papers should make significant corrections to page one stories on the front page itself, not buried somewhere deep inside the paper months or years later. That is, if a correction is offered at all; the Times eventually published half-hearted apologies for their errors in the Wen Ho Lee case and flaws in the WMD stories, but none for the smear against Clinton. Credibilty also must start on page one; why can't a newspaper -- particularly a paper as influential as the Times -- declare war on error?

Another fundamental media problem is the fast turnover of our modern news cycle, which doesn't give stories much time to be noticed before they sink below the horizon, probably lost forever. Usually blamed is the "24/7" pressure from TV and the 'net, but it's really the same game that's existed since the early Twentieth Century, when newspapers fought epic circulation wars, competing by churning out several daily editions that. each promised the very freshest news. Back then it was a destructive to good journalism, and it still is today; the result is a media serving up an unhealthy diet of celebs-and-sensation "junk food news," as Project Censored founder Carl Jensen dubbed it.

The punishing pace of the news cycle results in the crime of omission, a constant topic in these 404 Reports and other media criticism. But the real damage extends far beyond today's orphaned stories; also missing are followups on yesterday's big news. Remember the Christmas tsunami? Although the tragedy was the top story for days and an unprecedented number of Americans donated money to the relief effort, scant coverage has reported what's happened since -- that much of the aid never reached the people in need, and big countries welshed on their generous pledges.

Constantly watching the latest feed rolling off the wires lends editors to develop an odd myopia that prevents them from seeing what's really newsworthy. A remarkable example of this happened in the recent push and shove between readers and newspapers over the Downing Street Memo. As an avalanche of letter demanded coverage of the Memo, newsrooms simply didn't grasp why anyone would care about newly disclosed details of events dating back to 2002. The disconnect between readers and their newspapers was so great that Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank actually implied that the Memo wasn't newsworthy because everyone should already know that Bush was gaming the system after 9/11 to justify an attack on Iraq. Dana, you need to get out of the office more.

The tragedy is that newspapers don't have to run themselves to death chasing the news cycle to compete with broadcasting's "rip and read" headline news. Readers don't even want that; a 2004 Pew study found only 18 percent of the public care merely about headlines, and 40 percent wanted newspapers to provide thoughtful analysis (the rest wanted some combo of headlines and facts).

What would your favorite daily look like, in a brave new world of newspapering? For starters, readers would be offered regular installments about developing stories that have complex backgrounds. In this alt universe, papers would have mesmerized readers this summer by reporting the latest developments in the Jack Abramoff scandal. Here is a story that reads like a red-meat paperback thriller, complete with a unsolved, gangland-style murder of a partner following a shady business deal. An intimate to the top echelons in the Republican party -- his association with Karl Rove goes back to college days -- Abramoff funnelled millions in lobbying money from casino-rich Indian tribes to GOP politicians and front groups as well as supporting right-wing causes (among them a sniper school for Israeli colonists living in the West Bank). A new skeleton has tumbled from his closet almost every week recently; the latest is that those California and Mississippi tribes made hefty 2002 donations to the New Hampshire Republican party as it was running a "dirty tricks" operation, jamming Democratic party phone lines on election day. Abramoff's tale is probably the greatest political scandal since Iran-Contra, and likewise has so many characters and plot twists that readers need a running start to follow the action. But without ongoing coverage, understanding the most recent events is as hopeless as opening Charles Dickens' "Little Dorrit" to chapter 27 and trying to unravel what banker Merdle did to poor Mr. Clennam.

Newspapers in that better world would always try to help readers understand stories in context. Some possible changes are easy, and even could be made in time for tomorrow's editions:

|

| Researchers discovered that the permafrost of western Siberia's permafrost is thawing for the first time in 11,000 years. The melting peat bog, as big as France and Germany combined, may cause a catastrophic release of billions of tons of methane, a greenhouse gas 20 times more damaging than carbon dioxide |

Had the stories been presented together, they would have grabbed attention; but running them piecemeal -- or in the case of the American press, not at all -- the impact was small, narrowly limited in the U.S. to ardent bloggers and visitors to enviro websites. Lost was the chance to make an impression on a wide audience about a pressing global problem, and lost was a challenge to nay-sayers like President Bush who posture that "the jury's still out" about global warming.

They say recognizing your problem is the first step, and it's a positive sign that so many journalists are talking about the bleak future of newspapers. But the fundamental problem is that newspapers are working against their own interests in so many ways. Instead of endless hand-wringing about print media's possible demise in a competitive world with broadcast headline news or Internet news portals, the right question to ask is this: How to make a newspaper a better newspaper? (August 31, 2005)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

But that wasn't all the space news on that last weekend in July. By weird coincidence, U.S. researchers announced the very next day the existence of a tenth planet beyond Pluto. The unnamed planet is in the Kuiper belt, the cloud of debris orbiting the sun beyond Neptune that is the source of many comets. As such, there's some question whether it should be called a planet, and what meaning "planet" should have at all, considering there are probably many other underscovered objects like this.

How did the U.S. press cover the two stories? News about the tenth planet appeared on every newswire, which ensured that probably every newspaper in the country offered at least a short item about the discovery. The blanket coverage even made a few front pages, including the New York Times. Headline writers had a merry romp: "Puny Pluto Gets Big Brother; It's A Planet!" (Chicago Tribune), "By Jove, Let's Name A Planet!" (Hartford Courant), "Far-Out Dude: 10th Planet Discovered" (NY Post).

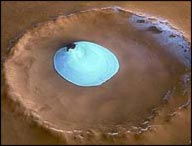

Coverage of the Martian ice discovery was the opposite. Although it was momentous news, it didn't appear on a single U.S. newspaper front page, despite that spectacular picture. It didn't appear inside those U.S. newspapers, either; not a single daily paper can be found that mentioned the discovery. There was no AP story, no Reuters or UPI coverage. All that can be found in the American mainstream press is a short item from the Bloomberg wire that was bundled with other items picked up by a few broadcast media websites.

So what happened? Why did the American media not only ignore the historic Martian water story, but featured another astronomical discovery of no lasting importance whatsoever?

The first culprit to suspect is the generally dismal quality of science reporting in the mainstream press, frequently lamented here in the 404 Reports. Was it simply that a "new" planet was viewed as more significant than an "improved" planet? Or maybe it was a lack of understanding of the importance of extraterrestrial water; longtime MONITOR readers may recall a nearly identical incident in 1998, when the press mostly ignored the discovery of water on the moon. The emphasis here is on mostly; despite competition from the peaking Lewinsky/impeachment story, that discovery was still widely covered, albeit in the back pages of newspapers and on the final segments of evening news broadcasts. Maybe that discovery didn't get the coverage it deserved, but it still wasn't ignored totally. (The media did completely overlook the important issue of who owns the rights to that lunar water, however.)

No, the finger of blame points directly to the weakness of most modern-day journalism: The Passive Press. The new planet story apparently received wider coverage because it was easier to report.

Take a look at the European Space Agency's press release, which should be preserved forever as a lousy example of how to communicate with people lacking a degree in astrophysics. Writing is dense with unnecessary detail: "The HRSC obtained these images during orbit 1343 with a ground resolution of approximately 15 metres per pixel." There's no mention of the significance of the discovery; no byline or name of a press contact, or any other information on how to reach someone for quotes or questions.

By contrast, the announcement of the new planet was slick and professional, using NASA's unparalleled PR machine to get the word out. A telephone press conference featured team leader Dr. Mike Brown, who has a knack for colorful quotes: "Get your pens; start rewriting the textbooks today." Also provided were interesting back stories of how Brown lost a planet-discovery champagne bet by a mere eight days, and how the team rushed to make the announcement because they feared an Internet hacker had stolen their research.

The planet story was a breeze to write -- quotes and details were presented to the media like a gift-wrapped package. In the other case, reporters needed to do a little research to find someone who could explain why Martian water is so important. This may have required a phone call to NASA or a query to the ProfNet service that serves as a matchmaker between journalists and experts of all types. There's even a new book out on the exploration of Mars ("Roving Mars," Steve Squyres/Hyperion), and you can bet that the publisher would've jumped at the chance to publicize the book with quotes from its author. As far as the craft of reporting goes, none of this was heavy lifting.

Or maybe the American press simply didn't cover the discovery because no one recognized its importance -- although it's depressing to ponder that the media might really be... well, incurious.

But it shouldn't take a science diploma to see how this discovery completely changes the future of human space exploration. With water easily available, permanent Martian colonies are possible, and not in some distant, sci-fi future; the main obstacle now is a spaceship that can get people there. Plentiful Martian water can supply greenhouses growing food, generators creating breathable air, hydrogen providing fuel.

The saddest part of this misadventure was the lost opportunity to rekindle the public's imagination. Americans read that weekend about the discovery of a remote lump of rock, fuzzy in the best telescopes, and with the zen-like quality of being important only because it existed. Imagine instead that we opened our Sunday papers to a vision of colonized Mars a few years hence, complete with an artist's rendition of ice-skating astronauts. (August 8, 2005)

Albion Monitor Issue 137 (http://www.albionmonitor.com)

All Rights Reserved.

Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format.