|

|

With the French army left largely to its own devices, torture and other atrocities became widespread, even commonplace. Torture, in particular, was institutionalized by the army. In the process, the senior ranks of the French military grew increasingly disenchanted with its civilian leadership in a manner reminiscent of the retired U.S. generals who called recently for the resignation of Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld. Eventually, senior military officers turned on the government and attempted to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle, an episode captured later by film director Fred Zinnemann in "The Day of the Jackal."

| |

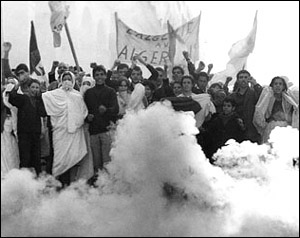

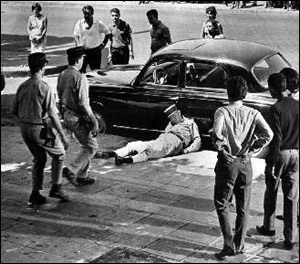

(All photos: "The Battle of Algiers")

|

Alistair Horne, a fellow at St. Anthony's College, Oxford, is the author of 19 books, many of which treat French military or political subjects. Published in 1977, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962 was immediately proclaimed by experts from all sides of the political spectrum to be the definitive history of the Algerian war. In rereading the book, the early praise seems justified as Horne does a superb job on detailing the Byzantine intricacies of the conflict with intelligence, style, and grace.

"Class Notes" is an innovative, sometimes provocative, series published by the Washington Post in which journalists visit the classrooms of government officials and Washington insiders teaching the next generation expected to join their ranks. Thomas E. Ricks, a Washington Post staff writer, published an article in the series on April 28, 2006, based on a visit to the School of Advanced Warfighting, Marine Corps University, in Quantico, Virginia. Sitting in on a course entitled "SAW 7202-06: ÔThe French Army at War in Algeria, 1954-1962,'" he discovered the French struggle against Algerian rebels had become a hot topic among officers deploying to Iraq.

Reflecting this interest, the present demand for used copies of A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962, now out of print, is so great that the few soft cover copies available on www.alibris.com are selling for up to $265. On Amazon.com, a used hardcover edition is offered at $280. I count myself fortunate to have retained a dog-eared old copy, purchased in the late 1970s when I was working in North Africa.

In his Washington Post article, Ricks indicated that the 11 military officers studying Algeria, which included eight marines, one army major, and one officer each from Australia and Italy, looked at the conflict from a variety of perspectives, always with a thought to its similarities and differences with Iraq. For example, both conflicts involved urban terrorism supported by remote desert camps, and both grew very unpopular at home. France deployed a huge conscript army in Algeria while the United States has depended heavily on National Guard and Reserve units, citizen soldiers, in Iraq. On the other hand, France was fighting to remain in Algeria while the United States hopes to withdraw from Iraq as soon as an independent and stable government is in place. The officers also discussed the heavy manpower demands of both conflicts as well as the widespread use of torture in Algeria. Ricks' article was not clear as to what conclusions, if any, were reached by the officers taking the course.

A member of the Italian Communist Party, Gillo Pontecorvo undertook his masterpiece, "The Battle of Algiers," the most atmospheric and forceful film about the war, under prodding from the Algerian resistance leader, Saadi Yacef. Banned in France for many years, the film suggests the French went too far in their widespread adoption of policies of torture, intimidation, and outright murder. That said, "The Battle of Algiers" is neither a propaganda piece nor a how-to-do-it manual. In the film, the leadership of the French army dissects and represses the insurgency as Algerian partisans plan and execute their actions, often using violent means to achieve their goals.

The Battle of Algiers was over by 1957, five years before the Algerian War ended, with the French successful in destroying the FLN resistance network operating in the Casbah, the city's ancient Muslim section. It was a pyrrhic victory at best. France ultimately lost the war, withdrawing in 1962 from a newly independent Algeria ruled by the FLN. The use of force may have been a tactical success, but it was clearly a strategic failure. It inspired support for nationalists in and out of Algeria, discredited the French army, led to domestic political scandals in France, and traumatized French political life for decades.

End Product

The Algerian War left some 30,000 French men and women dead, together with as many as one million Algerians. Over 800,000 European settlers, so-called pied-noirs, were driven from Algeria into exile. Algerian auxiliaries recruited by the French, known as harkis, were despized as collaborators by the independence movement. Largely abandoned by the French at the end of the war, they were hunted down and killed by the FLN. Estimates of their losses range from 10,000-150,000. Disputed statistics are only one of the highly-charged issues that perpetuate conflict over the war. The Algerian War also caused the fall of six French governments, resulted in the collapse of the Fourth Republic, returned Charles DeGaulle to power, and almost provoked a civil war in France.

| |

|

The French government never apologized for its conduct during the war, and official France continues to have difficulty dealing with the conflict. It was not until mid-1999 that the word guerre (war) was established officially to describe events in Algeria in 1954-62. In an article in the April 2001 issue of Le Monde diplomatique, journalist Maurice T. Maschino explored in detail the extent to which history textbooks in France still describe its broader colonial history as a "fine intellectual adventure" with a "broadly positive outcome." The war in Algeria is depicted as a struggle between Europeans, colons(colonists), and paratroopers on one side and Muslims, fanatics, and terrorists (never maquis, resistance fighters, or patriots) on the other. Most of the textbooks mention torture but play it down as an understandable reaction to the massacre of European civilians and a justifiable means to destroy FLN networks or to prevent bomb attacks.

Much like the Vietnam War haunts Americans, the horror and brutality of the Algerian War haunts the French people. The brutality of the war was again exposed in November 2001 when a former French general, who admitted in a book published in May 2001 to the torture and execution of dozens of Algerians during the war, was put on trial and found guilty. General Paul Aussaresses was charged, not with the acts themselves which had long been covered by an amnesty, but for publishing an unapologetic version of them in his book, Services Speciaux Algerie 1955-1957.

Expressing no remorse for his actions, either in the book or on the witness stand, General Aussaresses admitted to the summary execution of 24 men and to supervising the torture of dozens of others. Arguing torture was the best way to make a terrorist talk, he told the court his actions were justified, adding he would do the same again "if it were against Osama bin Laden." Of the hundreds of executions he ordered, the general added, "I was indifferent. They had to be killed, that's all there was to it."

A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962 remains a good read; however, whether or not it should be required reading for U.S. officers serving in Iraq, together with their civilian and military bosses in the White House and Pentagon, depends on the lessons learned. From the perspective of more than a half-century, the Algerian War might seem to some as a precursor to the amorphous struggles now raging in Afghanistan and Iraq, conflicts in which religious faith, imperialism, nationalism, and terrorism reach unimagined degrees of intensity, instead of what it was, the last colonial war. This may explain in part its popularity in the Bush administration.

| |

|

That said, any suggestion that the conditions the United States faces in Iraq mirror those the French encountered in Algeria is off the mark. If the White House is weighing the tactical choices reflected in A Savage War of Peace, the Algerian War would appear to exemplify what not to do in Iraq as opposed to being a user manual for U.S. forces. There is a certain allure to the use of brutal and repressive means to fight clandestine terrorists which some may find attractive; however, the French experience in Algeria demonstrates this is a false path to success. French tactics in Algeria lost the battle for the hearts and minds of Algerians, and in the end, the war itself.

Mounting evidence suggests that the Bush administration is drawing the wrong lessons from Algeria. To be successful in the war on terrorism, you must first win the battle of ideas. American tactics in Iraq, as symbolized by the abuse and humiliation of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison and the wanton and methodical murder of civilians at Haditha, suggest a breakdown in moral authority and leadership, similar to what the French experienced in Algeria.

"Combat Diary: The Marines of Lima Company," a two-hour documentary about an Ohio marine reserve unit which lost 24 men in Iraq, strongly reinforces this impression. Shown on Memorial Day weekend, this powerful window into the harsh reality of war includes several interviews with young marines who, out of anger and frustration, readily admitted at times to being on the brink of committing violent acts against Iraqi non-combatants.

In the case of Haditha, there remains an open question as to whether this was an isolated incident or the product of what is known as "command climate," the pressure from up-the-chain-of-command to produce results, pressure which can cause over-reaction as I witnessed first-hand as an army intelligence officer in the Vietnam War. The prolonged incarceration without trial of prisoners at Guantanamo and the policy of rendition simply compound the negative results of this unholy mix. By all means, read Alistair Horne's A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962, but read it not to learn how to win the war in Iraq and the broader war on terrorism, but how to lose it.

Article courtesy Foreign Policy in FocusRonald Bruce St John, an analyst for Foreign Policy in Focus has published extensively on Middle Eastern issues for almost three decades. He is the author most recently of the Historical Dictionary of Libya (1991, 1998, 2006) and Libya and the United States: Two Centuries of Strife (2002)

Comments? Send a letter to the editor.Albion Monitor

June 1, 2006 (http://www.albionmonitor.com)All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |

|