Which came first: media pressure or mental illness?

|

|

|

|

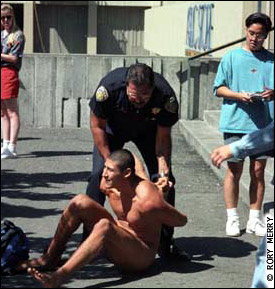

Andrew Martinez being arrested at UC Berkeley in 1992

PHOTO: Rory Merry by permission

|

[Editor's note: Andrew Martinez was found unconscious in his Santa Clara County solitary confinement jail cell on May 17 and died the following day. Authorities said Martinez, who reportedly suffered from a mental illness, apparently committed suicide by placing a plastic bag over his head. He was in custody because of assault charges resulting from a January fight at the halfway house where he was living.]

(PNS) --

Last

week an estranged man took his own life in prison -- but unlike the more than 1,200 suicides completed in confinement each year in the United States, this one will be remembered by many. Andrew Martinez had an a.k.a. to survive him: The Naked Guy.

Andrew became famous during my freshman year at UC Berkeley, in 1992. He wasn't hard to look at. He was a tall, lean man with lovely brown skin. On warm days, he'd stroll to campus wearing nothing but sandals and a backpack. When he got to class, he'd usually put on shorts before going inside. Media nationwide quickly picked up on the story, and he appeared in magazines and on several TV talk shows.

Andrew's cousin, whose name I don't remember now, lived in my dorm. She was a sweet girl, a good student from semi-rural California. She didn't tell people about her relation to this media star -- like him, she didn't appreciate or know what to do with his fame.

|

|

|

In my second year, I moved into the student co-op where Andrew lived among 80 other offbeat Berkeley students. I expected to feel intimidated by his passionate commitment to his cause, but by the time I met Andrew, he seemed to be struggling to keep the message of his nudity in his own voice.

The press and TV commentators used images of him to tell their own story. Rumors reformatted his words into political statements about our prudish American culture. I don't want to speak for Andrew, but all I ever understood was that he didn't want to wear clothes when it was warm out. His message wasn't "Ef you, I'm gonna walk around naked!" It was quieter, an invitation.

My most vivid memory of Andrew is his walking naked into the co-op dining room for breakfast with a plate of toast. He set the plate on the table, and his backpack on the floor. He pulled a small towel out of the backpack and placed it on the chair, with a dignified snap like a four-star restaurant waiter. Then he sat down to read the paper.

He cared about hygiene. Or, at least, he cared about our cares about hygiene. But he did this without being asked. He was respectful of us, his housemates, and he didn't seem mad at us for wearing clothes.

When I heard rumors later about his mental illness, I wondered what came first -- craziness, or fame?

Long after he left public nudity behind, Andrew was still sticking up for the principle of openness. He took out the concrete driveway at the co-op to create a garden. He felt entitled to eat out of the kitchen even after he'd moved out. I can picture a tug of war he had with the petite kitchen manager over a large block of cheese. Similar to how I read him on the nudity issue, he seemed simply to ask, "What's the big deal?"

I defend the spirit of Andrew's intentions. I think fame drove him over the edge. He lost himself in it. By naming him The Naked Guy, we all drove him crazy. I heard he eventually wanted to take it all back. He must have known it damaged him. If Andrew had been ugly, he might be alive today, because fame wouldn't have wanted him so badly -- certainly Playgirl wouldn't have wanted him.

Being in the headlines is the worst kind of fame, because there's no paycheck, no royalties. They take your picture, interview you, get the ratings and spit you out.

I think of actress Debra Winger, who left Hollywood for several years after an early boost to fame. She said, "No thanks," and settled on a suburban ranch on the East Coast with her family, no cameras in sight. Or of child stars like Drew Barrymore or Britney Spears, who for all we know might be crazy, but are too rich or too wanted to end up in halfway houses. Or Michael Jackson, whose well-documented downward spiral leaves little room for questions about the fallout of young stardom.

The tragedy of Andrew Martinez isn't simply that he had mental illness, or died young. It's that when he said, "No, thanks," fame replied, "Too late. You're mine now, but I'm giving you nothing to live on." We lost Andrew this week, but he lost himself years ago.

Comments? Send a letter to the editor.Albion Monitor

May 28, 2006 (http://www.albionmonitor.com)All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |

|