|

|

The Bush Administration's Afghan Spring

by Tom Engelhardt

|

READ

Afghan Situation Grim And Getting Grimmer

|

|

|

If

Iraq has been the disaster zone of Bush foreign policy, Afghanistan is still generally thought of as its success story -- to the extent that anyone in our part of the world thinks about that country at all any more. Before the invasion of Iraq, Afghanistan experienced a relative flood of American attention. It was, after all, the liberation moment. Possibly the most regressive and repressive regime on Earth had just bitten the dust. The first blow had been struck against the 9/11 attackers. The media rushed in -- and they were in a celebratory mood.

As Bush administration efforts quickly turned Iraqwards, however, so did media attention. By June 2003, just two months after the invasion of Iraq, the American Journalism Review tells us, "only a handful of reporters remained in the struggling country on a full-time basis, while other news organizations floated correspondents in and out when time and resources permitted." More recently, just Newsweek, the Washington Post, the Associated Press, and possibly the New York Times (which seems to have Carlotta Gall back on the beat) consider Afghanistan -- the devastated land that has been the crucible for, and breeding ground for, so many of the crises and problems of our era -- important enough to have full-time reporters assigned to it.

There was a burst of media attention last October for the Afghan presidential election, won by Hamid Karzai. It was a demonstration of something we've seen since in Iraq and elsewhere -- that people everywhere feel understandable enthusiasm at the thought of determining their own fates with their own hands (however limited their ability to do so may be in reality). It was, in fact, with the Afghanistan election that the Bush administration's "Arab Spring" blitz, its present success story about spreading democracy worldwide, with an emphasis on the Middle East, really began.

| |

|

|

Since then, what news Americans have gotten about Afghanistan has consisted largely of infrequent reports on the deaths of small numbers of American troops there; statements, interviews, and press conferences by various American generals or officials on the ever-improving situation in the country, or on the Pentagon's sudden willingness to tackle the drug problem there; pieces on "abuses" of Afghan prisoners by American troops or CIA agents; or statements about how we must stay in the country until a struggling new democracy truly takes root in that impoverished land. Throw in the odd propaganda visit by an American dignitary and you more or less have Afghan news as it exists in this country. After all, in most of Afghanistan there are no reporters. Even the 5,000 European troops guarding the capital, Kabul, under the NATO banner have but recently begun to make it beyond Kabul's bounds. The Americans alone have given themselves the run of the country and they have generally preferred to keep the news to themselves.

The last wash of Afghan news came when, after a year of planning, Laura Bush made it there for six hours this spring to "offer support for Afghan women in their struggle for greater rights," to meet President Hamid Karzai, and to have a meal with American troops at Bagram Air Base. (Headlines were of the "Laura Bush Pledges More Aid for Afghanistan," "Laura Bush in Afghanistan to Back Women's Education," "First Lady Drops in on Afghanistan" variety.) Standing next to an Afghan woman, shovel in hand, she also had her picture taken and disseminated in the American press. The caption in my hometown paper says she was "posing for a photograph at a women's dorm at Kabul University and planting a tree." As a photo, nationalities aside, it might easily have graced the pages of Soviet Life magazine and come from a distant imperial era.

| |

READ

Countryside Revolt Feared If Crackdown On Afghan Opium

|

|

|

DRUGS

So

Afghanistan has once again become the land that time forgot. Given the present Bush democracy blitz and given the country's "success" -- a "struggling" or "nascent" democracy or "semi-democracy," liberated from one of the worst regimes on Earth and helped back onto its feet by 17,000-plus American troops stationed on its territory, it seems a case worth revisiting. What follows is the best assessment I can offer -- from this distance -- based at least to some extent on more fulsome reporting done for media outlets outside the United States.

| |

A soldier from the 29th Infantry Division of the Virginia National Guard stoops to enter and search the home of a suspected Taliban member in Afghanistan on June 4, 2005

|

When you begin to look around, you quickly find that just about everyone -- Bush proponents and critics alike -- seems to agree on at least some of the following when it comes to the experiment in "democracy" in Afghanistan: The country now qualifies, according to the Human Development Index in the UN's Human Development Report 2004, as the sixth worst-off country on Earth, perched just above five absolute basket-case nations (Burundi, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Sierra Leone) in sub-Saharan Africa. The power of the new, democratically elected government of Hamid Karzai extends only weakly beyond the outskirts of Kabul. Large swathes of Afghanistan are still ruled by warlords and drug lords, or in some cases undoubtedly warlord/drug lords; and while the Taliban was largely swept away, armed militias dominate much of the country as they did after the Soviet withdrawal back in 1989. In addition, a low-level guerrilla war is still being run by elements of the former Taliban regime for which, in areas of the South, there is a growing "nostalgia."

Women, outside a few cities, seem hardly better off than they were under the Taliban. As Sonali Kolhatkar, co-Director of the Afghan Women's Mission, told Amy Goodman of Democracy Now!:

"We hear... about [how] five million girls are now going to school. It is wonderful. When I was in Afghanistan, I noticed that in Kabul, certainly schools were open, women were walking around fairly openly with not as much fear. Outside of Kabul, where 80% of Afghans reside, totally different situation. There are no schools. I visited the Farah province, which is a very isolated, remote province in western Afghanistan and there were no schools except for the one school that Afghan Women's Mission is funding that is administered by our allies, the members of RAWA. Aside from that one school for girls, there are no schools in the region. And so we hear all of these very superficial things about how great Afghan women are, you know, the progress they're making. The UN just released a report recently on Afghanistan where they described Afghanistan's education system as, quote, 'the worst in the world.' And, you know, we never hear that. Our media, when they covered Laura Bush's trip, will not mention, will not do their homework, and will not mention these facts."

According to the UN report, "Every 30 minutes a woman in Afghanistan dies from pregnancy-related causes... 20 percent of children die before the age of five... [and] the poorest 30 percent of the population receive only 9 percent of the national income, while the upper 30 percent receive 55 percent."

Reconstruction throughout the country has been faltering; funds promised by international bodies and states have not been delivered in anything like the amounts agreed upon; the new Afghan National Army, being trained by the Americans, is a weak reed when it comes to national (or local) security; most non-governmental aid organizations, many of which largely abandoned the country because it was so perilous for their workers, have yet to return or are just barely testing the waters again; and what economic growth there is seems to exist largely thanks to the drug trade, which is said to account for 60 percent of the country's gross domestic product.

Having cornered most of the world's supply of opium poppies and a growing slice of its heroin-production facilities, Afghanistan seems to be well on the way to becoming the globe's narco-state par excellence. It has "bumper harvests that far exceed even the most alarming predictions," according to "senior Pentagon officials" quoted by Thom Shanker of the New York Times.

Paul Rogers, the canny geopolitical analyst for the openDemocracy website, sums the situation up this way:

"Afghanistan is returning to levels of production typical of the chaotic period after the withdrawal of Soviet military forces in 1989. According to United Nations sources, opium poppy cultivation from 2003-04 increased by 64%; around 120,000 hectares (300,000 acres) are now under cultivation. The most recent UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report, Afghanistan: Opium Survey 2004, finds that Afghanistan now accounts for 87% of the world's illegal production of opium... On the basis of the 2004 estimate, 2.3 million people in over 330,000 households are involved in production, 10% of the Afghan population."

According to the Times' Shanker, "One military officer who has served in Afghanistan gave a more pointed assessment: 'What will be history's judgment on our nation-building mission in Afghanistan if the nation we leave behind is Colombia of the 1990s?" It's an apt analogy, though economically Colombia looks like paradise compared to Afghanistan. Until recently, the Pentagon actively resisted in any way interfering in the burgeoning drug trade -- in part, undoubtedly, because it was funding local warlords involved in the trade. The recent organized murder (on the eve of his departure from the country) of a British development specialist, Steven MacQueen, who had been involved in a small-scale project to wean Afghan farmers from opium growing was but one ominous sign of the direction the new democracy seems to be taking.

The Karzai government is weak indeed. Parliamentary elections have just been postponed for the third time -- until September. Warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum, the new defense minister, is probably a bona fide war criminal (and former American ally) with 30,000 militia under his command. And this is but to scratch the surface of a nearly lawless land destroyed by decades of war against the Soviets, of civil war among warlords, of war and rule by the Taliban, and of bombing and invasion by the United States (which paid the Northern Alliance and other warlords to do most of its war-fighting work for it and has been dealing with the results of that decision ever since).

The Afghan story may, in many ways, be the saddest tale on Earth today, which, given the role of the country in our recent history, may also make it the most dangerous story around. Who now remembers a time in the 1950's and early 60's when, in peaceful Cold War competition for influence with the Soviets, we were building ranch-style houses near Kandahar in a country that had a middle class and was reasonably prosperous. Today, it's as if that took place on the other side of the moon. But let's not assume that everyone other than the drug lords in Afghanistan is unhappy. Take the Bush administration and the Pentagon, for example.

| |

READ

U.S. Military Bases Growing Worldwide

|

|

|

MILITARY BASES

Just

the other day, Air Force Brigadier General Jim Hunt gave an interview in which he announced an $83 million upgrade for the two main U.S. bases in Afghanistan: Bagram Air Base, north of Kabul, and Kandahar Air Field in the South. A new runway to be built at Bagram will be part of a more general effort, said Hunt: "We are continuously improving runways, taxiways, navigation aids, airfield lighting, billeting and other facilities to support our demanding mission."

The general offered some other figures relating to that mission: "150 U.S. aircraft, including ground-attack jets and helicopter gunships as well as transport and reconnaissance planes, were using 14 airfields around Afghanistan. Many are close to the Pakistani border. Other planes such as B-1 bombers patrol over Afghanistan without landing."

Strange, those 14 airfields, since in Iraq the U.S. has reportedly been building up to 14 permanent bases (or "enduring camps"). You have to wonder whether there's something in that number. In certain numerological systems, 14 is evidently associated with "addiction." The question is: What exactly are America's air-field upgraders and base builders addicted to?

Gen. Hunt typically explains the addiction, or mission, this way: "We will continue to carry out the... mission for as long as necessary to secure a free and democratic society for the people of Afghanistan." But here's the curious thing: We're ramping up our air bases in Afghanistan at the very moment when our generals are also claiming that the left-over guerrilla war being carried out by Taliban remnants is on the wane. After another of those American drop-ins on Hamid Karzai and his country, General Richard Myers, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs recently announced from the relative safety of Kabul airport that Afghanistan was "secure" ("Security is very good throughout the country, exceptionally good"), even as he suggested that "the United States is considering keeping long-term bases here as it repositions its military forces around the world." In the process, he also discussed what he and others politely call a future "strategic partnership" between the Pentagon and Karzai's Afghanistan (which is a little like saying that a lion and a mouse are considering forming an alliance).

In recent months, guerrilla attacks had indeed fallen off radically, though a particularly fierce Afghan winter may in part have been responsible. As spring arrives, the pace of the fighting seems again to be picking up somewhat. Still, if you were considering Afghanistan in isolation, the logic of our generals and officials might seem to indicate that, as the war against Taliban and al-Qaeda remnants winds down, so should American troop strength and base positioning. That on bases at least, the opposite seems to be happening might lead you to scratch your head -- especially if your only source of information was our largely demobilized press in which the news is reported (when it is) more or less country by country and days can pass before you run across a piece that includes, say, three or four countries, no less discusses the actual geo-political look of things. Throw in the fact that Pentagon basing policy is considered an inside-the-paper story for policy wonks and that U.S. bases -- wherever located -- are not considered subjects worthy of significant coverage.

But, of course, our strategists in Washington pay notoriously little attention to the press and, from the beginning, they've been thinking in the most global of terms as they plan various ways to garrison the parts of the world -- essentially, its energy heartlands -- that matter most to them. And if you turn, for instance, to a striking piece in the Asia Times by Ramtanu Maitra, U.S. scatters bases to control Eurasia, you can get a sense of what all this Pentagon basing activity really adds up to. Maitra reports that a decision to set up new U.S. military bases in Afghanistan -- up to 9 scattered across in six different provinces -- was taken during Donald Rumsfeld's drop-in on Kabul Airport in December. These small bases, expected to be small and "flexible," are to be part of a new American global-basing policy that "can be used in due time as a springboard to assert a presence far beyond Afghanistan."

As Maitra points out, Sen. John McCain, the number two Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, while on a Kabul drop-in of his own and after talks with Karzai, proclaimed himself committed to a "strategic partnership that we believe must endure for many, many years" and assured reporters that the "partnership" should include "permanent bases" for U.S. military forces. (He later backtracked on the bases, his statement perhaps being a bit too blunt for the moment.)

For our Afghan bases to make much sense, you have to consider as well, those fourteen (or so) permanent bases in Iraq, our many other Middle Eastern bases, our full-scale access to three or more Pakistani military bases, our penetration of the once off-limits former SSRs of Central Asia, including the use of an air base in Uzbekistan and the setting up of a base for up to 3,000 U.S. troops at Manas in impoverished Kyrgyzstan (where "the Tulip Revolution" has just ejected a corrupt pro-Russian regime). In fact, you have to see that from Camp Bondsteel in the former Yugoslavia to the Manas base at the edge of China, the United States now effectively garrisons most of the heartland energy regions of the planet.

As Maitra comments,

"Media reports coming out of the South Asian subcontinent point to a U.S. intent that goes beyond bringing Afghanistan under control, to playing a determining role in the vast Eurasian region. In fact, one can argue that the landing of U.S. troops in Afghanistan in the winter of 2001 was a deliberate policy to set up forward bases at the crossroads of three major areas: the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia. Not only is the area energy-rich, but it is also the meeting point of three growing powers -- China, India and Russia.

"On February 23, the day after McCain called for 'permanent bases' in Afghanistan, a senior political analyst and chief editor of the Kabul Journal, Mohammad Hassan Wulasmal, said, 'The U.S. wants to dominate Iran, Uzbekistan and China by using Afghanistan as a military base.'"

| |

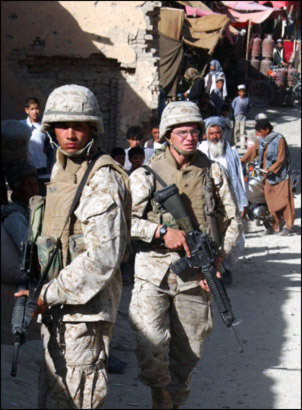

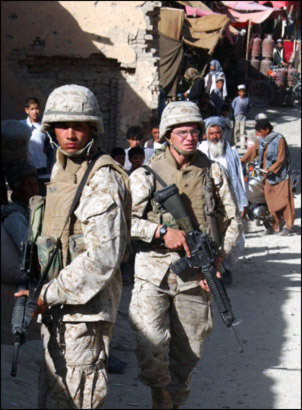

Army National Guard soldiers and Marines conduct foot patrols on the streets of Ghazni, Afghanistan, on July 26, 2004

|

Throw in our access to potential bases in the former Eastern European satellites of the former Soviet Union (Rumania and Bulgaria in particular) and you have the Pentagon positioned in quite remarkable ways not just in relation to the oil lands of the planet, but also in relation to our former superpower adversary. People ordinarily say that the Soviet Union "fell" in 1990 as the Berlin Wall came down, but in fact the Soviet Union has never stopped "falling." Susan B. Glasser and Peter Baker, until recently Moscow bureau chiefs for the Washington Post, quote "analysts" as now speaking of "'the second breakup of the Soviet Union.' Some were even daring to ask the ultimate question: Could Russia itself be next?"

Just in the last year, we've seen "the Rose Revolution" in Georgia, "the Orange Revolution" in Ukraine, and now "the Tulip Revolution" in Kyrgyzstan, all heavily financed and backed by groups funded by or connected to the U.S. government and/or the Bush administration. As Pepe Escobar of the Asia Times writes:

"The whole arsenal of U.S. foundations -- National Endowment for Democracy, International Republic Institute, Ifes, Eurasia Foundation, Internews, among others -- which fueled opposition movements in Serbia, Georgia and Ukraine, has also been deployed in Bishkek [Kyrgyzstan]... Practically everything that passes for civil society in Kyrgyzstan is financed by these U.S. foundations, or by the U.S. Agency for International Development (U.S.AID). At least 170 non-governmental organizations charged with development or promotion of democracy have been created or sponsored by the Americans. The U.S. State Department has operated its own independent printing house in Bishkek since 2002 -- which means printing at least 60 different titles, including a bunch of fiery opposition newspapers. U.S.AID invested at least $2 million prior to the Kyrgyz elections -- quite something in a country where the average salary is $30 a month."

American policy-makers have been aided greatly by the harsh and heavy-handed rule of corrupt local leaders and by the crude politics of Russian President Vladimir Putin who, in his attempt to protect the Russian "near abroad," has positioned himself to fail in country after country. As Ian Traynor of the British Guardian writes, "He has managed to manoeuvre himself into the unenviable position of being identified as a not very effective supporter and protector of unsavoury regimes throughout the post-Soviet space." And, of course, they have been aided by the genuine urge of peoples from Kyrgyzstan to Ukraine not to be under the thumb of various Putin-style semi-autocrats -- or worse.

(You could say, in a way, that the "near abroads" of both former superpowers have been falling away for years now; for, in a similar manner, an urge to break away and implement new forms of democratic and economic independence from Washington's diktats has been evident in our former Latin American "backyard" -- from Argentina to Bolivia, Brazil to Venezuela -- the difference being that the Latin American version of this has lacked the funds from a distant superpower.)

The result of all this has been that, with the exception of Belarus and Siberia, Russia has been pushed back into something reminiscent perhaps of its borders several centuries ago. This has to be a dream result for former anti-Soviet cold warriors like Dick Cheney and Condi Rice. After all, they've accomplished what even the most rabid cold warriors of the early 1950s could only have dreamed of. They have turned "containment" into "rollback."

In the meantime, the Pentagon, firmly ensconced in an ever expanding set of bases in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia, has Iran militarily encircled. With approximately 160,000 troops (not counting mercenaries) and all those planes and helicopters, it now occupies two countries right in the oil and natural gas heartlands of the planet.

In fact, though their situations are many ways different, there are certain (enforced) similarities between Iraq and Afghanistan. In neither country, did we arrive with an exit strategy, because in neither case did we plan on departing. Both countries are ruled by exiles, effectively installed by us. Realistically speaking, both the government in Baghdad's Green Zone and the one in Kabul are, in the kindest of terms, "wards" of the United States. Both lack the ability to defend themselves. The Iraqi government is essentially installed inside a vast American military base and, as Maitra points out, "the inner core of Karzai's security is run by the U.S. State Department with personnel provided by private contractors." (As a little thought experiment, try to imagine this in reverse. What would we make of an American president whose Secret Service was made up of foreigners hired by the government of Hamid Karzai?)

In both countries, democratic elections of a sort were conducted not just under the gaze of, but under the actual guns of, the occupiers (though when it comes to the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, the Bush administration quite correctly insists that democratic elections shouldn't be run in an occupied country). Above all, in both countries, the Bush administration is eager for a "strategic partnership," which means that its officials are eager to remain free to act beyond anyone's laws, in any manner of their choosing, and with almost complete imperial impunity.

| |

READ

Iraq Prison Abuse Mirrors Problems In Afghanistan Lockups

|

|

|

JAILS

In

recent months, the best news reporting on Afghanistan has focused on the detention and jailing practices of Americans in that country and has been based largely on limited investigations conducted by one or another part of our government. A December Washington Post piece by R. Jeffrey Smith (General Cites Problems at U.S. Jails in Afghanistan), while discussing "a wide range of shortcomings in the military's handling of prisoners in Afghanistan," managed to mention that we have "roughly two dozen" (count 'em: 24) prisons in that country. Smith's piece began:

"A recent classified assessment of U.S. military detention facilities in Afghanistan found that they have been plagued by many of the problems that existed at military prisons in Iraq, including weak or nonexistent guidance for interrogators, creating what the assessment described as an "opportunity" for prisoner abuse."

In such pieces, there are always "shortcomings" in American practices or dangerous "opportunities" still available for "abuse." (The word torture is seldom used in the U.S. media in such situations). The major abuses almost invariably turn out to have been largely over by the time the investigation being reported on took place. The Smith piece ends typically: "U.S. forces have 'tightened up procedures for training up our people to handle and care for the prisoners,' Keeton said. They now have standard operating procedures in place, she said, and mechanisms to enforce them." All of which proves true until the next batch of horrors pours out.

A recent Dana Priest piece for the Post (CIA Avoids Scrutiny of Detainee Treatment) on long past crimes against Afghans has a similar flavor. ("The CIA's inspector general is investigating at least half a dozen allegations of serious abuse in Iraq and Afghanistan, including two previously reported deaths in Iraq, one in Afghanistan and the death at the Salt Pit, U.S. officials said. A CIA spokesman said yesterday that the agency actively pursues allegations of misconduct.") Such acts (or crimes) are normally dealt with in the American press as individual cases -- just as recently stories of the various "extraordinary renditions," global kidnappings of terror suspects, and the like, many of whom then passed through Afghan jails, have trickled out largely as individual tales of terror and mistreatment, even if sometimes then toted up. They are essentially part of what really is the "bad apple" school of journalism, largely based on various military or official investigations of what the military, intelligence agencies, and the Bush administration have done.

To see the larger patterns in this you usually have to look elsewhere. For instance, Emily Bazelon of Mother Jones magazine had this to say (From Bagram to Abu Ghraib):

"Hundreds of prisoners have come forward, often reluctantly, offering accounts of harsh interrogation techniques including sexual brutality, beatings, and other methods designed to humiliate and inflict physical pain. At least eight detainees are known to have died in U.S. custody in Afghanistan, and in at least two cases military officials ruled that the deaths were homicides. Many of the incidents were known to U.S. officials long before the Abu Ghraib scandal erupted; yet instead of disciplining those involved, the Pentagon transferred key personnel from Afghanistan to the Iraqi prison... Even now, with the attention of the media and Congress focused on Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo, the problems in Afghanistan seem to be continuing."

As it turns out, the problems are indeed continuing and in a form that simply cannot be read about in the mainstream media in this country. Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark went to Afghanistan for the British Guardian and traveled the country investigating American detention practices to produce a piece, "One huge U.S. jail," that really should be read in full by every American. They do what any good reporter should do: They attempt to put together the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle, take in the overall picture, and then draw the necessary conclusions.

They start by saying, "Washington likes to hold up Afghanistan as an exemplar of how a rogue regime can be replaced by democracy. Meanwhile, human-rights activists and Afghan politicians have accused the U.S. military of placing Afghanistan at the hub of a global system of detention centers where prisoners are held incommunicado and allegedly subjected to torture." Then, based on their own investigations, Levy and Scott-Clark lay out the geography of detention in America's Afghanistan:

"Prisoner transports crisscross the country between a proliferating network of detention facilities. In addition to the camps in Gardez, there are thought to be U.S. holding facilities in the cities of Khost, Asadabad and Jalalabad, as well as an official U.S. detention center in Kandahar, where the tough regime has been nicknamed 'Camp Slappy' by former prisoners. There are 20 more facilities in outlying U.S. compounds and fire bases that complement a major 'collection center' at Bagram air force base. The CIA has one facility at Bagram and another, known as the 'Salt Pit,' in an abandoned brick factory north of Kabul. More than 1,500 prisoners from Afghanistan and many other countries are thought to be held in such jails, although no one knows for sure because the U.S. military declines to comment."

They conclude that -- U.S. courts having made Bush administration detention centers in Guantanamo, Cuba, vulnerable to potential prosecution, "what has been glimpsed in Afghanistan is a radical plan to replace Guantanamo Bay... [as an] offshore gulag -- beyond the reach of the U.S. constitution and even the Geneva conventions." They add:

"However, many Afghans who celebrated the fall of the Taliban have long lost faith in the U.S. military. In Kabul, Nader Nadery, of the Human Rights Commission, told us, 'Afghanistan is being transformed into an enormous U.S. jail. What we have here is a military strategy that has spawned serious human rights abuses, a system of which Afghanistan is but one part.' In the past 18 months, the commission has logged more than 800 allegations of human rights abuses committed by U.S. troops."

| |

READ

The "Great Game" Continues -- With U.S. In Charge

|

|

|

THE GREAT GAME

In

the current Great Game of armed geopolitical chess the Bush administration is playing, it's not quite clear who is on the other side. Is it Vladimir Putin and his desire to create a new, more modest version of the Soviet Union? Is it China -- or rather, the anticipation of a future oil-crazed Chinese move into the region? Is it largely to isolate Iran and finally create American-style regime change there? Or is it all of the above?

| |

A young Afghan boy sits with U.S. Army Sgt. Jason Manning as he enjoys tea and bread with local citizens in Gardez, Afghanistan, Dec. 18, 2004

|

Speaking of Russian-American competition, it has, it seems, become modish for American officials from our Secretary of Defense to assorted generals to brag that, in Afghanistan, we did in weeks what the Soviets couldn't do in years. What the Soviets couldn't do in years, of course, was successfully conquer Afghanistan. (Despite present appearances, needless to say, it's not yet clear that the Bush administration has done so either.)

This seems to me a bizarre, yet telling expression of American imperial pride; even a reasonable description of Afghan realities, as seen from Washington. After all, the Soviets too swore they were "liberating" the Afghans from an oppressive way of life as they staked their imperial claim on the country back in the late 1970's. In fact, the largest American base in Afghanistan, Bagram Air Base, is often referred to in the press as "the former Soviet base." If, to put this in context, we went back to the Soviet period and observed Soviet troops in Afghanistan doing what American troops are now doing (as, in fact, they did, right down to the grim detention centers), we would certainly have employed other terms than "democracy" or even "strategic partnership" to describe what was going on.

It may be the case that Afghanistan will prove the perfect Bush "democracy." It had an election and sooner or later will undoubtedly have more of them. Its resulting government remains weak, malleable, and completely dependent on American forces. The U.S. military and our intelligence services have had a free hand in setting up various detention centers, prisons, and holding camps (where anything goes and no law rules) that add up to a foreign mini-gulag stuffed with prisoners, many not Afghan, beyond the reach of any court. Our fourteen airfields and growing network of bases and outposts are now to be "upgraded" as part of a 'strategic partnership" with an Afghan government that we put into power and largely control. These bases, in turn, should serve as a launching pad for controlling the larger region, and the detention and torture centers as suitable places for the unruly of the area. Afghanistan, in short, is in the process of becoming an electoral- narco- gulag- permanent-base dependency, and so qualifies as a model democracy, suitable to be spread far and wide.

If you wanted to come up with a little formula for what's happened you might put it this way:

Afghan Spring

American freedom of action

Afghan democracy

American air bases

So the Afghanis go to hell while making drugs their export of choice; the Bush administration gets its bases; and if you happen to be one of the American conquerors of that benighted land, you don't return home to parade down a major thoroughfare in your chariot with your war booty and slaves before you (and a slave by your ear whispering about the vanity of conquerors) ˆ la the Romans, but you do get an American version of the same. You can go out on the lecture circuit and make a fortune, or become a play-by-play TV commentator for the next American war to come down the pike, or if you're Tommy Franks, former CENTCOM commander and victorious general in our Afghan border war, you might be "tabbed to join the board of directors of Outback Steakhouse Inc." with a modest $60,000 annual compensation (plus expenses and fees). Could life be sweeter -- or meatier? Could Outback Franks be next? Will Outback open a Bagram outlet? Stay tuned as geopolitics meets the chain restaurant.

This article first appeared in Tomdispatch.com and is reprinted by permission

Tom Engelhardt, who runs the Nation Institute's Tomdispatch.com ("a regular antidote to the mainstream media"), is the co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of The End of Victory Culture, a history of American triumphalism in the Cold War.

© Tom Engelhardt

Comments? Send a letter to the editor.Albion Monitor

July 14, 2005 (http://www.albionmonitor.com)All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |

|