|

|

The Battle For Israel's Future And Soul

by Neve Gordon

|

READ

The Notorious Ariel Sharon

|

|

|

| |

The Wall under construction in E Jerusalem in early 2004

|

Two

weeks after 60,000 Likud Party members voted against a pullout from the

Gaza Strip, about 150,000 Israelis filled Rabin Square in Tel Aviv, calling

on Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's government to proceed with the withdrawal

plan. Those opposing the pullout from Gaza support the vision of a Greater

Israel, while those favoring the pullout support the state of Israel. The

first group believes that without Gaza, Israel will be destroyed; the second

believes that with it, Israel will be destroyed.

Ironically, many of those who packed the Square also participated in a famous protest in 1982 -- only then, the

demonstration was against Sharon and his invasion of Lebanon. The fact that many of those who protested

against Sharon "the war criminal" that year took to the streets to support him

and his unilateral plan to withdraw from the Gaza Strip in 2004 warrants an

explanation. Has Sharon undergone a metamorphosis in the 22 years separating

these two protests? Or, has the Peace Now rank- and- file who

chanted in the 1982 protest changed over the years?

Following the establishment of the first Likud government in 1977, Sharon

hoped that Prime Minister Menachem Begin would make him defense minister. He

was dismayed when Ezer Weizmann received that portfolio, while he was

appointed minister of agriculture. Soon thereafter, the peace agreement with

Egypt began to unfold. Weizmann, who hoped to include the Palestinians

within the accords, opposed the settlement project then underway; he opined

that Israel should withdraw from occupied Palestinian territories within the

framework of a peace treaty. Sharon, on the other hand, voted against the

withdrawal from Sinai and wanted to preempt the possibility of any future

agreement based on trading land for peace. Accordingly, as chair of the

government's Settlement Committee, he initiated a massive settlement

enterprise in the Occupied Territories. Whereas Israel erected 20

settlements in the West Bank between 1967 and 1976 (in addition to those

built on confiscated Palestinian land around East Jerusalem), within less

than four years Sharon managed to build 62 new settlements, completely

changing the landscape of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Since then, Sharon

has been considered the father of Israel's unruly settlement project.

Sharon's commitment to a Greater Israel, however, preceded his political

career. While still a general in the Israeli military, Sharon created an

alliance with Gush Emunim (in Hebrew, Bloc of the Faithful), the highly

efficient settler movement. "I confess that I am the initiator of the idea

of establishing Jewish settlements in the Strip," he said in a 1973

newspaper interview, right after he resigned from serving as the general in

charge of Israel's Southern Command. Sharon went on to explain: "I

established Kfar Darom [the first settlement in the Gaza Strip] and I

established Netzarim, and encircled their territory with fences."

In August 1981, Sharon became defense minister. Four years earlier, he had

told an Israeli reporter that "the Arab states are swiftly preparing for

war, and we are sitting on a barrel of explosives wasting our time on

nonsense. The Arabs," he continued, "will launch a war in the summer or the

fall." The war did not come, at least not until Sharon assumed office. The

story of how Sharon led Israel into Lebanon, hoping to establish a puppet

government in order to preempt attacks from the north, is by now well-known.

Also well-known is the Sabra and Shatila massacre of September 1982, and the

findings of the Israeli inquiry commission, headed by Chief Justice Yitzhak

Kahan, which led to Sharon's resignation. The Kahan Commission did not,

however, manage to change Israeli political reality. It took 17 more years

before Israel finally withdrew its troops from Lebanon, after thousands of

civilians and soldiers lay buried in the ground, hundreds of thousands of

people had been displaced, and much of Lebanon was in ruins. Moreover, the

Commission did not blame Sharon for the war or his role in the massacre, and

he was never expelled from the political realm.

In February 2001, 18 years after the Kahan Commission published its

findings, Sharon finally made his ultimate comeback, winning direct

elections and becoming the prime minister of Israel with an unprecedented

62.4 percent of the vote. Two years later, he was reelected in a landslide

victory, making him the first premier to be elected to a second term since

Begin in 1981. Given his history in Lebanon and his more recent notoriety

for visiting the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount under heavy armed guard in

late September 2000, sparking Palestinian demonstrations that mushroomed

into the second intifada, many commentators were surprised at the avuncular

image he chose for himself during his first campaign. Was this a new Sharon,

they wondered, or the same old Sharon? The prime minister's allies on the

Israeli right wondered the same thing after he used the word "occupation" to

describe the Israeli military presence in Palestinian towns and again after

the promulgation of his "disengagement" plan.

But to focus on Sharon's persona is to miss the point. Over the past year a

significant change has begun to take place in Israel, one that also helps to

explain why the same people who protested against Sharon in 1982 flocked to

Rabin Square in 2004 to support his withdrawal plan. The change has to do

with a growing rift between two ideologies that for years had been cemented

together: the messianic ideology of a Greater Israel and the militarist

ideology of a Greater Israel. The connection of these two ideologies, now

unraveling, had been one of the astounding historic accomplishments of the

settler movement: Gush Emunim.

| |

Gush Emunim: Land as a bridge

|

|

|

While

secular Zionism conceived the return of Jews to Palestine in standard

Western nationalist terms, Gush Emunim's founders claimed that the heart of

Zionism lies in following the religious duty to settle the land. Zionism,

the leaders of Gush Emunim maintained, is not simply one national movement

among many others, but rather a movement blooming from the revival of Jewish

religious values. It is, as Michael Feige points out in his 2002 book, "One Space,

Two Places" (available in Hebrew only), a messianic movement without a messiah, since

the utopian vision will be realized not after the appearance of a God-like

figure, but following the complete control of the land of biblical Israel.

| |

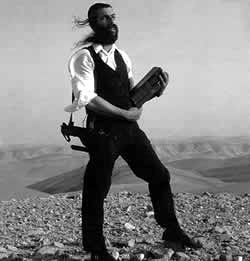

Popular images such as this glorified the view of the settlers as pioneers settling a wilderness, holding a Torah while an Uzi is slung over the shoulder

|

Early on, though, the movement's leaders realized that a messianic ideology,

on its own, would not be enough to accomplish cultural and political

hegemony in Israel, and that Gush Emunim would have to transform the

collective Israeli consciousness if the movement were to realize its

political objective of gaining control over Greater Israel. Religious

rhetoric, by itself, would not justify the erection of Jewish settlements in

the Occupied Territories to a largely secular public. Consequently, Gush

Emunim integrated the modern nationalist discourse into its messianic

ideology, while also adopting a militarist ideology. This is precisely where

Sharon enters the picture.

As a secular Jew who grew up in Mapai (the precursor to the Labor Party),

Sharon should ostensibly have had very little in common with Gush Emunim.

Yet, the land Israel occupied in 1967 created a bond between the military

man and the religious movement. To be sure, Sharon's connection to the West

Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem was never based on religious belief or

messianic conviction. Rather, the attachment was informed by a particular

military point of view that conceives of territory as the essential

ingredient of security.

Even before Sharon resigned from the military, an

alliance was born between him and Gush Emunim. The settlers' bloc aspired to

build on the lands Israel had occupied to fulfill a religious duty, while

Sharon thought that settlement in and control over the Occupied Territories

was the way to secure the state of Israel. Gush Emunim provided the cadres

for new Jewish settlements and Sharon provided both the military

justification, and, at various points in his career, the authority to seize

lands owned by the occupied Palestinians. Not surprisingly, every time the

legality of the settlements has been challenged before Israel's High Court

of Justice, "security concerns," not religious edicts, have been used to

justify the dispossession of the indigenous inhabitants.

Already in 1974, when the first government of Yitzhak Rabin sent the

military to dismantle the Jewish outpost of Elon Moreh, Sharon, who was no

longer in the army, protected the settlers with his own body. He told an

Israeli reporter that it was an "immoral military command, and it is

necessary [for soldiers] to refuse such orders. I would not have obeyed such

orders." After years of disputes in the courts, Elon Moreh was recognized by

the state (at an alternative location), becoming a symbol of settler

resolve. For Sharon the command to evacuate the outpost near the West Bank

town of Nablus was immoral because, in his view, it undermined Israel's

security objectives; for Gush Emunim it was immoral because it frustrated a

religious duty.

Rapidly, though, the distinction between the two ideologies was blurred --

security concerns and fundamental religious duties were interlocked in such

a way that it became extremely difficult to make out the difference between

the two. Gush Emunim's ability to secularize and militarize its messianic

aspirations is in many respects the secret behind its success in changing

the Israeli collective consciousness and in attaining both cultural and

political hegemony. The integration of the two ideologies also served

Sharon's personal objectives, not least because the rabid nationalism it

produced helped to broaden the constituency supporting him during his races

for political office.

| |

Israel, said one of Gush Emunim's founders, was heading toward an abyss

|

|

|

For

thirty years, Gush Emunim (which eventually was institutionalized and

transformed into the Yesha Council, Yesha being the Hebrew acronym for

Judea, Samaria and the Gaza Strip) and Ariel Sharon were bedfellows.

Together, they managed to accomplish a great deal. If in the early 1970s

there were no more than a few hundred Jewish settlers living in a handful of

settlements, today one cannot travel more than a few kilometers within the

Occupied Territories without running into a settlement. Taken together, the

settlements house about 400,000 settlers. The settlement project has been so

successful that several political analysts no longer consider the two-state

solution a tenable option. Moreover, the Yesha Council's political clout by

far exceeds the size of its constituency, in many ways resembling the

influence wielded by the kibbutzim during the heyday of Mapai. There are far

more members in today's Knesset favoring a Greater Israel than in any

previous legislature, and the settler movement is probably the most powerful

lobby group in Israel.

But while that movement's leaders may look back to the past with a sense of

satisfaction, most of them look forward to the future with great despair.

Speaking at Ben-Gurion University in the spring of 2004, Eliakim Haetzni,

one of Gush Emunim's founders, told a room full of professors that the

movement's settlement enterprise was on the verge of destruction. Israel, he

maintained, was heading toward an abyss. This statement was, to say the

least, perplexing to those in the room who share Haetzni's sense of despair,

but from a diametrically opposed perspective, since they hail from the

opposing political camp within Israel. What could explain this shared

sensation of defeat among the mutual antagonists?

There is no doubt that Sharon's unilateral plan to dismantle the Gaza

settlements and withdraw the troops who guard them, while closing of all the

Strip's borders -- including access from air and sea -- is informed by the

Greater Israel paradigm. But Sharon's notion of a Greater Israel is founded

on militarism, as opposed to the messianic beliefs espoused by Haetzni and

Gush Emunim. For years these two ideologies overlapped. Now, the reemergence

of the difference between them is threatening the settlers' hegemony.

Sharon has finally admitted that the Gaza Strip is not a military asset. He

knows that within the Strip the Palestinians will always have a demographic

advantage, and because the criterion informing his judgment is ultimately

military and not religious, he is no longer willing to allocate exorbitant

state resources to protect the handful of Jewish settlers living there.

Advocating a withdrawal from the Strip represents the first move toward a

divorce between the two ideologies.

Sharon's proposal, though, is also about annexation. One clause stipulates

that areas within the West Bank "will remain part of the state of Israel,

among them civilian settlements, military zones and places where Israel has

additional interests." The Bush administration supported this clause,

legitimating Sharon's request to annex de jure what has already been annexed

de facto. The idea is to provide legal standing to almost all the 220,000

Jewish settlers living in the West Bank and the 180,000 living in East

Jerusalem, and, in this way, reduce the possibility that they will need to

return to Israel proper under any future agreement.

| |

Haetzni's despair

|

|

|

Why,

one might ask, did the West Bank settlers reject Sharon's unilateral

plan? After all, in return for a pledge to relocate 7,500 settlers, the

Israeli premier induced Bush to acknowledge the legality of 400,000 settlers

and, in this way, helped to realize the dream of a Greater Israel. Sharon's

pledge, moreover, has only been approved in principle by the Israeli

cabinet, and the prime minister must return to the cabinet in March 2005

before actually dismantling a single settlement.

The answer is complex. On one level, the settlers know -- better than anyone

else -- that in the Occupied Territories the rule of law matters much less

than facts on the ground. For the settlers, a withdrawal from Gaza would

create a dangerous precedent. It would mark the first time since 1948 that

Jewish settlements were dismantled within the context of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict. If settlements can be dismantled in the Strip,

they can be uprooted in the West Bank as well. On a deeper level, the

settler movement realizes that Sharon is creating a rift between the

messianic and militarist ideologies. If Sharon convinces the Israeli public

that the religious agenda is unconnected to security, the movement will lose

much of its clout. This helps explain Haetzni's despair.

| |

Palestinian man tries to save an olive tree uprooted by Israeli bulldozers constructing The Wall

|

Although Sharon may have discarded the messianic ideology, he intends to

pursue his political objectives until the very end. Accordingly, he has

substituted for the messianic ideology a new and extremely efficient

weapon -- the separation barrier. Made up of a series of fences, trenches,

walls and patrol roads, the barrier was initially supposed to separate

Israel proper from the Occupied Territories, yet it is actually being built

deep inside Palestinian lands. It will create facts on the ground that will

affect any future arrangement between Israel and the Palestinians.

Although in many parts the barrier separates Palestinians from Palestinians,

the militarist ideology has convinced the public that it is built to

separate Israelis from Palestinians -- a classic example of an ideological

superstructure camouflaging the material developments on the ground. The

barrier being erected is qualitatively different from a barrier whose

function is to demarcate a border between two countries; it is much more

like the barriers used to create prisons. Moreover, if Sharon pulls it off,

about 50 percent of the West Bank will be annexed to Israel and the

Palestinian "state" will be made up of a number of districts that are not

contiguous. In apartheid-era South Africa, such regions were called

bantustans.

| |

READ

The Challenge to the Two-State Solution

|

|

|

Tragically,

many of the 150,000 peaceniks who demonstrated in support of

Sharon's withdrawal plan also back the separation barrier and do not really

care where it passes. Whereas Sharon may have given up on holding 100

percent of the land between the Mediterranean and the Jordan, and therefore

abandoned Gush Emunim's version of the Greater Israel ideology, many liberal

Israelis are willing to support Sharon's 50 percent plan for a Greater

Israel, replacing the two-state solution mantra with a new buzzword --

"separation." The details about how to separate are not important. All these

liberals want is an immediate divorce, and Sharon, they think, can perform

the ceremony. In terms of militarist ideology, certain elements within Peace

Now hold views that are in many ways similar to Sharon's.

Peace Now was founded in the late 1970s by a group of reservist officers.

Although their aim was to pressure Israel to reach peace with Egypt and its

other Arab neighbors, including the Palestinians, these doves also derived

inspiration from tenets underlying the Jewish state that are

non-universalistic. Peace Now ends its major rallies with Israel's national

anthem, "Ha-Tikvah" (The Hope), which begins like this: "As long as the

Jewish spirit is yearning deep in the heart / With eyes turned toward the

East, looking toward Zion / Then our hope -- the 2,000-year old hope -- will

not be lost / To be a free people in our land / The land of Zion and

Jerusalem."

These words, written in 1886 by Naphtali Herz Imber, were intended for Jews

only and certainly exclude the 20 percent of the Israeli citizenry that is

Palestinian. Given what transpired after the song was written, the anthem

helps to perpetuate the Zionist myth that described the return of Jews to

Palestine as a return of "a people without a land to a land without a

people."

Although Peace Now avers that it recognizes the "fact that there are two

peoples in this land, Palestinians and Jews, each with a history, claims and

rights," in its activities the group fails to acknowledge the 1948

catastrophe of the Palestinian people, approaching the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict as if it began in 1967.

This historical bias has helped to render the Palestinian citizens of

Israel, as well as the pre-1967 Palestinian refugees, invisible. Moreover,

this bias underscores Peace Now's unwillingness to confront history from the

standpoint of the oppressed, which is a necessary component in every

dialogic attempt to bring peace. So while Peace Now continues to distrust

Sharon and vocally criticize his settlement policies, many of its leaders

and cadres now support the premier's call for separation, as opposed to

negotiation. They are also willing to "compromise" on the amount of land

Israel returns.

What Sharon and the Israeli peaceniks who support the separation barrier

neglect to see is that while the barrier imprisons the Palestinians, it is

also encircling Israel, turning it, as it were, into an island, as opposed

to a state among states in the Middle East. The crux of the matter is that a

worldview based solely on militaristic concerns is destined to be myopic.

Haetzni may be right to despair of his messianic vision's power to drive

Israeli policy in the Occupied Territories. But regardless of whether Sharon

manages to implement his withdrawal plan, the vision of a Greater Israel, as

opposed to a state of Israel, has, for the time being, triumphed. That

triumph, in turn, helps to explain why the Israeli peace camp that does not

support separation is also in despair.

Neve Gordon teaches political science at the Ben-Gurion University of the

Negev in Israel

Reprinted by special permission of the

Middle East Reasearch and Information Project (MERIP)

Comments? Send a letter to the editor.Albion Monitor

July 5, 2004 (http://www.albionmonitor.net)All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |

|