Reagan, AIDS, & CBS

by Jeff Elliott

|

by Jeff Elliott |

|

Grab

your eraser and scratch out this entry in The Great Book Of Cliches: "There is no such thing as bad publicity." CBS proved that false when it yanked "The Reagans" from its schedule just two weeks before the mini-series was to be broadcast, after an outcry from conservatives.

Grab

your eraser and scratch out this entry in The Great Book Of Cliches: "There is no such thing as bad publicity." CBS proved that false when it yanked "The Reagans" from its schedule just two weeks before the mini-series was to be broadcast, after an outcry from conservatives.

"This decision is based solely on our reaction to seeing the final film, not the controversy that erupted around a draft of the script," read a Nov. 4 statement by the network. "Although the mini-series features impressive production values and acting performances, and although the producers have sources to verify each scene in the script, we believe it does not present a balanced portrayal of the Reagans for CBS and its audience. Subsequent edits that we considered did not address those concerns." By any measure, that's quite a craven statement. Saying that the script contains verifiable events yet is not a "balanced portrayal" hints that there's something nasty and dishonest about the film. Was Nancy Reagan to be filmed in ominous shadows to emphasize her reputation as "the Dragon Lady?" Was there a stage direction calling for the president to doze off during diplomatic events? (Oh, wait, he did that -- including during his personal audience with the pope.) Not at all -- the script actually treats the Reagans quite gently and with respect. But at the same time, the screenplay does not fawn over the couple, or reduce their very real love story to a maudlin tearjerker. Controversy flamed over "The Reagans" as critics griped that it was cruel to profile a man with end-stage Alzheimer's and unable to defend himself, particularly against bits of dialogue that were invented by the writers. Pious Reagan never would have said "goddam" as he did in the screenplay, they insist. Nor would the Hollywood oldtimer with so many gay friends have been so mean-spirited to those dying of AIDS, defenders say. A throwaway line from the script, "They that live in sin shall die in sin," became the center of the furor. The scene found on page 171 is set in the Presidential limo as Nancy and Reagan glide down a Beverly Hills boulevard, Nancy recalls her gay hairdresser, who had recently died of "you know what."

"He was sick for months, but I never knew. Nobody ever told me," she says.The critics are right: This scene's a fake, as is the dialogue. As far as anyone knows, there was never any limo hand-patting while the President chided his wife about biblical punishment and AIDS. But the phony dramatic moment is NOT a cheap shot against Reagan; it's a display of generosity by the scriptwriter. What the man really did during those years was monsterous and unforgivable -- and, it seems, is now history lost to a generation that admires Reagan as its venerable grandfather. But as author Randy Shilts noted in "And The Band Played On," his history of AIDS: "He was the man who had let AIDS rage through America, the leader of the government that when challenged to action had placed politics above the health of the American people."

|

|

When

Ronald Reagan took office in January, 1981, AIDS was nearly unknown; barely more than a handful of Americans had died from the mysterious disease. In the course of the next year, it became apparent that it was becoming a public health emergency. At the first Congressional hearings on the epidemic in April 1982, the Centers For Disease Control (CDC) predicted that tens of thousands would be affected by the disease, which was considered invariably fatal.

The unlikely hero of the Reagan years turned out to be Dr. C. Everett Koop, the Surgeon General. Koop was first viewed as a nut-job by many in the Public Health Service, in part because of his insistence that all employees wear their Navy uniform at least once a week. (Commissioned by Congress in the 19th century, PHS is not part of the Navy or any other branch of service, but employees have full military benefits and the right to wear the uniform, although few did.) His nomination to the post was also opposed for months by women's groups and medical professionals because of his outspoken views against abortion. Koop had called it "infanticide" and "euthenasia," and appeared in an infamous anti-abortion film where he is seen standing in the desert surrounded by dolls that symbolize children not born because of abortion. Koop grasped the threat that AIDS represented, but found himself shutout from policy discussions. Years later, he confirmed what gay activists always assumed -- that Reagan officials didn't care about curing AIDS as long as it was mainly gays that were infected. "...Because transmission of AIDS was understood primarily in the homosexual population and in those who abused intravenous drugs, the advisors to the president, took the stand, they are only getting what they justly deserve... the domestic policy people, as well as the majority of the President's cabinet, did not see any need to come to grips with AIDS." While the Reaganites didn't care much for finding a cure, they approved of the discovery of a blood test for the virus. In the mid- 1980s, conservatives and the religious right began calling for compulsory testing, public identification, and even quarantine or tattooing anyone found to be HIV-positive. (There were even calls for quarantines of all of San Francisco and New York City.) What they didn't want was sex education that taught people how the virus spread. As a result, the U.S. was only industrialized Western nation without an AIDS education program by 1987. Koop spent two years working on his official report on AIDS, which ran counter to everything that the Reagan administration wanted. Koop called for AIDS education "at the earliest grade possible" and widespread use of condoms. Knowing that he would never get approval for a report like that, he bravely tricked the White House, as he recalled later:

The official response to AIDS, as far as our government was concerned, hinged on two meetings of the Cabinet. The first was just before the AIDS report was released by me to the public. And the second was in May of 1987, a meeting of the entire Cabinet with the President. In each of these meetings, I had to skate on rather thin ice and do it fast because I had to get by political appointees who placed conservative ideology above saving lives. The 1986 Surgeon General's Report was a landmark event in the history of the epidemic. At the International Conference on AIDS the following year, Koop was greeted like a rock star by the thousands of researchers and political activists. "Stop it! You're embarassing me!" He shouted, as the crowd roared. The next day, Vice President George H.W. Bush addressed the same conference and called for mandatory testing. As he spoke, many in the audience stood and turned their back to him in contempt. Koop may have been the champion that day, but there was little cheering as repressive measures followed in the weeks after. The Senate voted for mandatory testing of all immigrants and cutting funds for AIDS education aimed at gays. Three states -- Minnesota, Texas, and Colorado -- passed laws enabling police to indefinitely quarantine AIDS victims.

|

|

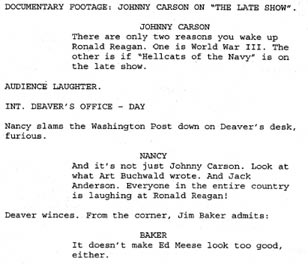

Where

was Reagan during all this? If there ever was a time when great national leadership was needed it was during these years, as the death toll from the disease steadily climbed with no apparent end. But Reagan -- always dubbed the "Great Communicator" -- didn't say a word. Year after year, Reagan remained silent; by the time he finally mentioned AIDS in 1987, an average of nine Americans had died for every day that he had been in office.

Where

was Reagan during all this? If there ever was a time when great national leadership was needed it was during these years, as the death toll from the disease steadily climbed with no apparent end. But Reagan -- always dubbed the "Great Communicator" -- didn't say a word. Year after year, Reagan remained silent; by the time he finally mentioned AIDS in 1987, an average of nine Americans had died for every day that he had been in office.

Why did Reagan remain silent for so long? Koop later said that "domestic policy folks in the White House isolated Ronald Reagan from the whole subject of AIDS," which is no surprise; Reagan was frequently kept out of the loop on important policy matters, as was revealed during the Iran-Contra hearings. It is not even certain whether Reagan officially intended for his Surgeon General to prepare his AIDS report; as Koop tells the story, the commission came from an off-hand comment made during a 1984 visit to the Department of Health and Human Services: "Among things, he said 'I'm also asking the Surgeon General to prepare a special report on AIDS.' That was it. There was never any formal request. It's a good thing I went to the meeting. It's a good thing I wasn't sleeping." Apologists for Reagan have made much over his old friendship with Rock Hudson to show that he wasn't a homophobe (although that doesn't necessarily reveal anything about his attitude towards people with AIDS). They note that the President personally called the actor when he was in Paris being treated for AIDS in 1985. But when Reagan phoned in June, only four people knew that Hudson had AIDS, and his publicist was working overtime insisting that the illness wasn't the virus. Hudson had personally told Nancy Reagan that he had caught a "flu bug" while filming in Israel. It was a full month later before the world learned that Rock Hudson was dying of AIDS. There were no sympathy calls or letters from Reagan after this became public. We do know that Reagan was remarkably ill-informed about the disease as late as December, 1985. His former doctor, Brigadier General John Hutton, recalled that Reagan asked him about the disease: "It's a virus, like measles? But it doesn't go away?" Not once did Reagan discuss AIDS with Surgeon General Koop. Neither of these incidents shed light on the "live in sin - die in sin" line in the script, but Reagan did make comments on AIDS that reflect his religious views. "I have always though the world might end in a flash, but this sounds like it's worse," he told Doctor Hutton. And later, in May, 1987, biographer Edmund Morris writes that Reagan said "maybe the Lord brought down this plague" because "illicit sex is against the Ten Commandments." That month, Reagan also delivered his only speech on AIDS. Exactly what he said is not available; the Reagan Library has not transcribed it -- nor is it listed by the Library as a "major" speech of his career. But witnesses said that not once in his speech did Reagan mention gays, although they were by far the greatest majority of vicitms, and the population that health workers needed most to reach. News reports say that he cracked a few jokes, called for manditory testing but not education or more funding. The Los Angeles Times quoted Dr. Mathilde Krim, one of the co- founders of AmFAR: "He started off quite nicely, talking about using compassion and taking care of people and not discriminating against them. But then he talked about knowing that promiscuity causes AIDS. That raises a red flag with people. When he talked about caring for people with dignity and kindness, that was fine," she added. "But then he mentioned the final judgment being up to God. That implied a lot to a lot of people." The next day, activists rallied in Lafayette Park across the street from the White House, chanting "History with recall, Reagan did the least of all." Reagan was still making jokes about AIDS late in his presidency, yet also wrote a compassionate 1988 letter to Elizabeth Glaser, whose daughter had just died from the disease, which her mother contracted from a blood transfusion. A couple of years later, Reagan filmed a public service announcement for the Pediatric AIDS Foundation setup by Glaser. Was it significant that Reagan's only personal show of sympathy went to Glaser and her child, who contracted AIDS via a medical procedure and not something that the religious right called a sin? |

|

Exactly

why CBS decided to cancel the mini-series is a mystery. Some media critics have pointed out that the media giant Viacom might have wanted to appease the Bush administration, which is currently behind efforts to ease restrictions on how many stations one company may own. With currently 39 TV stations and 175 radio stations nationwide, Viacom is one of the very few players who would benefit greatly under those rules.

Of course, no one outside of CBS had actually seen the film being so sharply criticized, and few had read the script until a copy began circulating in late October, when the NY Times and conservative gadfly Matt Drudge revealed the AIDS quote and other snippets sure to draw ire. (Thanks to Salon, a version of the complete script became available online Nov. 7, three days after CBS cancelled the broadcast and two weeks after conservatives began complaining that the film was a hatchet job.) But the whole script shows that Reagan apologists indeed had much to fear. While the scandal of Reagan's treatment of AIDS was dodged, the script gives full measure to the Iran-Contra scandal. A striking scene opens the second night of the mini-series, as Sen. John Tower confronts Reagan: "Mr President, as head of the Presidential Commission to investigate Iran-Contra, I'm here to tell you of our findings. One year ago, you personally approved the sale of anti-tank missles to Iran for the purpose of exchanging arms for hostages. You knew that Iran was on the United States' list of terrorist nations, and you knew that Congress had enacted an embargo against Iran. Nevertheless, you defied the United States Congress, and you defied the law."

Reagan's left hand twitches. Tower sees it, but continues: "The money from the arms sales -- $38 million -- was channeled through a covert network of dummy corporations; $4 million was diverted to the Nicaraguan Contras. Of the remaining $34 million, a majority wound up in private pockets. In conclusion, Mr. President, the action that you ordered has not only destroyed this country's foreign policy, it [has] turned us into the laughing-stock of the Middle East, and the world." The script calls for Reagan to look lost and frightened, as Tower begins speaking to him gently, as if he were a child: "I know you don't remember, Mr. President, but the Commission has ample evidence. We have memos, we have testimony. Whether or not you remember it now, there was a time when you knew everything." That scene crystallizes what Republicans want to whitewash about Reagan: That he was deeply involved in a serious crime that could have led to impeachment, had he not claimed to have forgotten key decisions made just a few years earlier. And claiming not to remember those events meant either that he was lying (3 out of 5 Americans thought so at the time) or that he probably wasn't competent to serve as president. So here's the likely real scandal: CBS was cowed to suppress the film not because it took great liberties with literal historical accuracy, but because it revealed such painful truth. The myth of the Golden Age of Reagan that conservatives are now pushing might not survive that dose of reality. The screenplay never directly tackles the issue of Reagan's mental acuity, but presents scenes that leave interpretation to the viewer. Given that no one knows if Reagan was actually competent or not, it is the wise path to take. The script ends with the final minutes of the Reagan's tenure in the White House; Nancy finds him standing by a window. "How in the ever-loving world did we get here?" He asks. "It doesn't matter. We're going home." She takes him in her arms and they begin to slowly dance. Fade out.

Albion Monitor

November 10, 2003 (http://www.albionmonitor.net) All Rights Reserved. Contact rights@monitor.net for permission to use in any format. |